The Lever of Possibility

The clock on the Idea Mill’s wall ticked past two in the afternoon when Michael slipped his badge into the reader and felt the soft green light flash “ACCESS GRANTED.” He paused at the threshold of the automotive bay, the smell of motor oil and fresh-cut metal greeting him like an old friend.

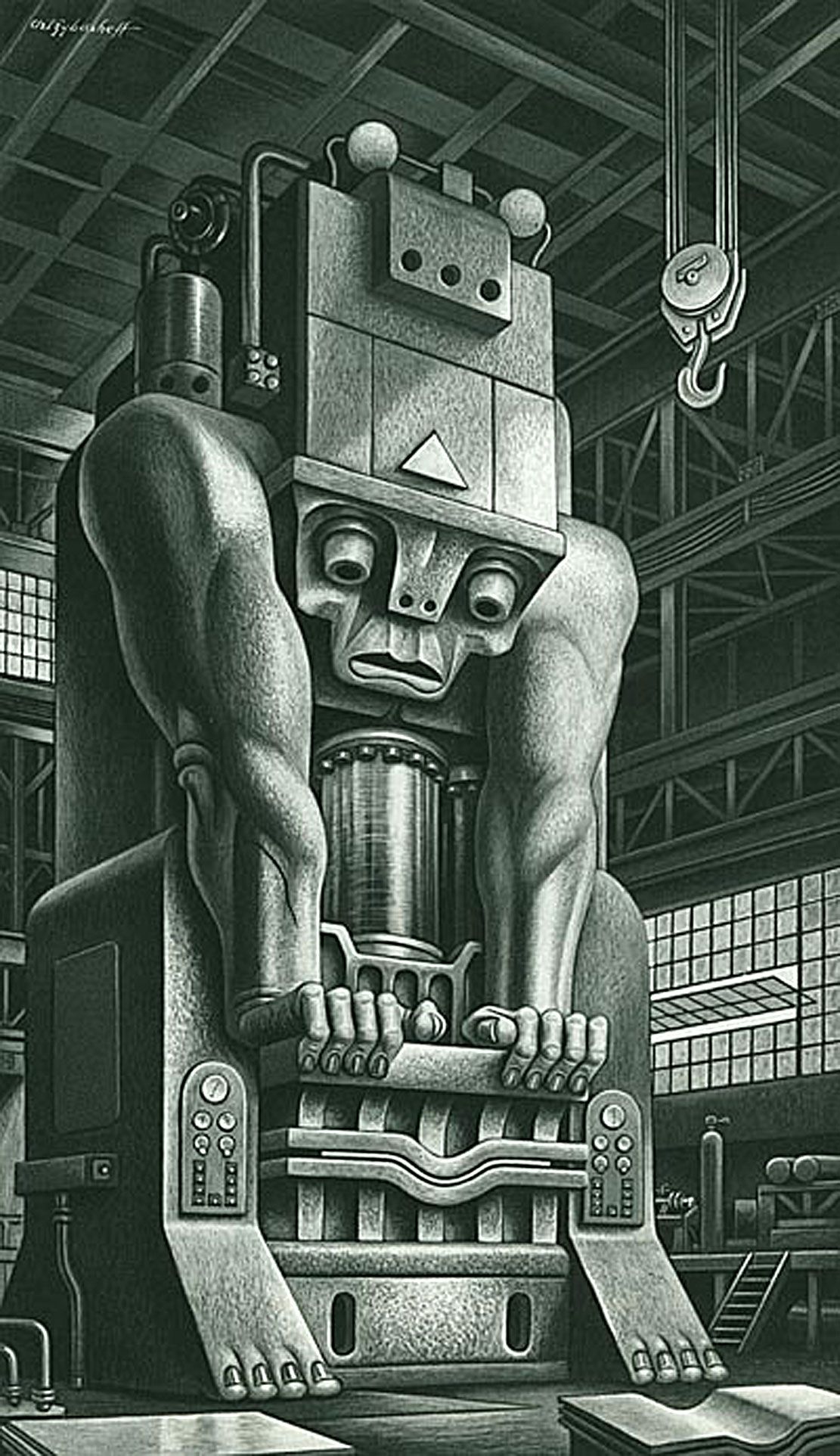

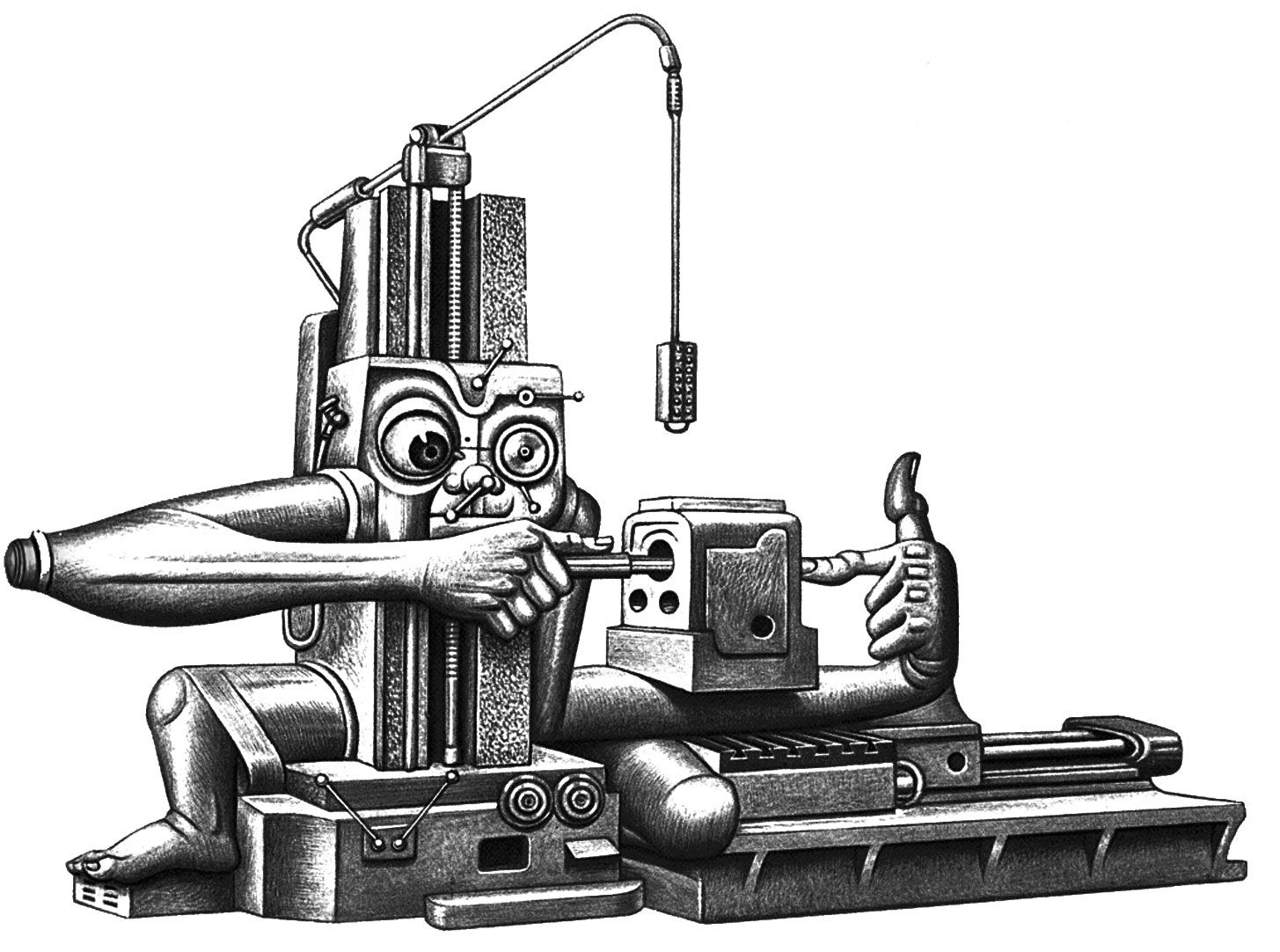

A hulking figure stood bent over a workbench, the silhouette of a leather jacket and shaved head catching the fluorescent glare. The man’s shoulders were as wide as an ox, his forearms thick as a 2 liter bottle. Yet when he looked up, his eyes crinkled in a grin that softened the intimidating exterior.

“Hey, kid,” the man rumbled, wiping grease from his hands onto a rag. “You look like you’ve got something on your mind.”

“I… I need a new brake lever for my bike,” Michael blurted, suddenly aware of how ridiculous it sounded to himself. “The store only sells whole bikes now. I can’t afford that.”

The man laughed, a deep, resonant sound that made the nearby metal tools seem to vibrate. “I’m Matthew. Machinist, Engineer, and Mentor. I’ve spent my life making practically all of the things, and I’ve seen a lot of people try to fix what the market says is ‘un‑repairable.’ Let’s see if we can’t turn that brake lever into a ‘possibility’”

Michael felt a wave of relief. He had imagined the lever countless times while riding his battered red Schwinn up the hill behind his house, the squeak of the old metal arm echoing in his ears. He hadn’t a clue how to start, but now there was someone who could help him make sense of the chaos in his head.

Sketches on a Napkin

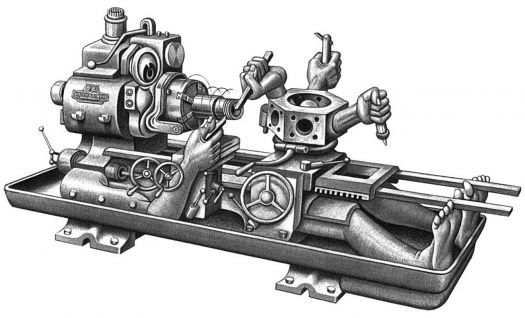

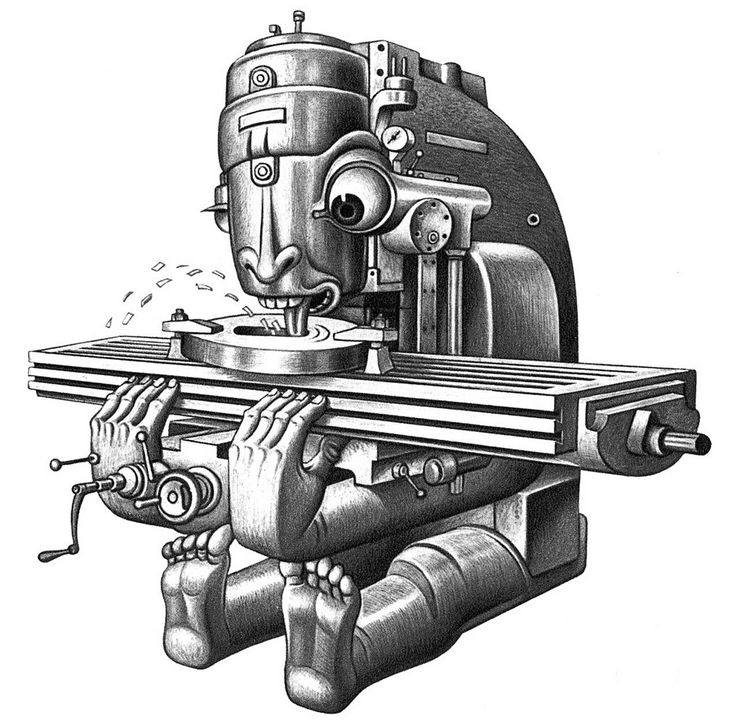

Matthew led Michael to a sturdy workbench cluttered with calipers and hand tools, a set of micrometers, and a battered but well‑maintained CNC mini‑mill. He pulled out a sheet of graph paper and a mechanical pencil.

“First things first,” Matthew said, tapping the paper. “You need a design. Sketch what you think the lever should look like. Don’t worry about perfect lines; just get the shape out of your brain and onto the paper.”

Michael’s hand shook a little as he traced a rough outline: a curved arm that would hook onto the brake housing, a pivot point for the cable, and a finger‑friendly grip. He added a small ridge where his digit could rest.

“Nice start,” the man said, nodding. “Now we’ll take that sketch and turn it into a 3D model. The good thing about the Idea Mill is we have a printer that can handle composite filaments—carbon‑reinforced nylon. Strong, light, and perfect for a bike part that needs to survive a lot of force and even some crashes.”

He reached for his tablet, launched Fusion 360, and began sketching over Michael’s drawing. As the lines formed into a solid model, Matt explained the basics of stress analysis.

“Bike levers see a lot of tension when you squeeze them. We’ll add internal ribs—little triangular walls inside the part—to keep the stiffness high and the stress low. The carbon fibers in the filament will take most of the load, while the nylon gives us a little flex or elasticity, so it won’t snap in an impact or cold weather.”

Michael watched the virtual model spin, the ribs popping up like a honeycomb under a microscope. He felt a flicker of excitement—this was more than a doodle on a napkin; it was a blueprint for something he could actually hold.

The Coffee Nook: New Friends and Old Stories

Around three o’clock, the coffee nook buzzed with the clatter of mugs and the low hum of conversations. The scent of espresso swirled with the faint aroma of fresh‑cut wood from the adjoining workshop. Michael followed the sound of a barista’s laugh and found a small table where a teenage boy was carefully tapping a wooden stick with a mallet.

“Erika!” the boy called, waving a bright green tote bag.

Erika, the barista with a cascade of red curls and sparkling green eyes, flashed a warm smile. “Luke! What’s on the agenda today?”

Luke, a lanky fourteen‑year‑old with a smudge of sawdust on his cheek, grinned. “Custom hockey stick for next season. I’m trying to get the curve just right for my left‑hand slap shot.”

He gestured to a CNC router in the opposite corner of the building, where a tall, thin man with a subtle limp was feeding a piece of maple into the machine.

“Mike,” Luke introduced, “he’s my guide. Retired carpenter, knows every grain of wood like it’s a family member.”

Mike, his lanky frame wrapped in a faded denim shirt, chuckled. “You’re making a stick that’ll make the other kids wish they’d learned to skate, huh?”

Luke nodded, eyes gleaming. “I need it to be light but strong. I heard the printers can make a carbon‑reinforced nylon grip, too.”

Erika poured a chocolate-almond-milk smoothie for Michael, the foam cup’s cap forming a tiny gear silhouette. “You look like you’re working on something serious,” she said, sliding the cup across the table.

Michael hesitated, then told her about his broken brake lever and the plan to print a new one. Erika’s eyebrows rose. “That’s a solid project. If you need any help with the printer, Tyler’s the man in the 3D printing hub. He’s a former oilfield millwright—knows how to keep things running under pressure.”

Mike, listening from the side, added, “If you need a quick jig to hold the lever while you test it, I can help you mill one out of pine. It’ll be cheap, and you can use it to make sure the geometry is right before you commit to the final print.”

The conversation turned into a rapid exchange of ideas. Luke showed Michael a CAD file of his hockey stick’s shaft, while Mike sketched a simple clamp that could secure the lever’s pivot point during testing. Erika offered a protein‑packed snack bar, and Michael felt the knot of anxiety loosen just a little.

When the coffee shop’s timer chimed, signaling a shift change, a tall, athletic man strode in—Tyler, the 3D printing guide. He wore a navy T‑shirt with a stylized gear logo and a pair of well‑worn work boots, his jeans were still marked with faint oil stains from his days in the oilfields.

“Afternoon, Michael,” Tyler said, his voice low but enthusiastic. “Heard you’re about to print a bike brake lever. Let’s make sure the printer is ready for the composite filament.”

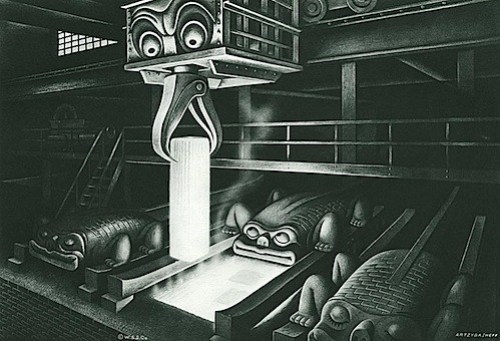

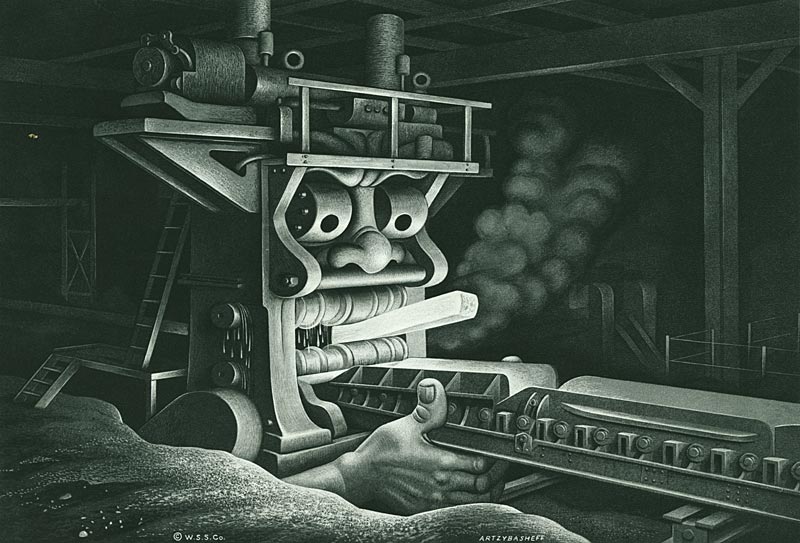

He led Michael to the Print Farm, where three Bambu‑style printers stood like silent giants. The largest of them, a matte‑black machine with a spacious build volume, was already warm from a recent print.

“We’ll be using Carbon‑Nylon called PA6-CF,” Tyler explained, pulling a spool of sparkly, charcoal‑colored filament from a cabinet. “It’s got carbon fiber chopped up into the polymer. Gives you about 30% higher tensile strength than regular PLA, and it’s lighter too.”

He showed Michael the printer’s extruder, pointing out the hardened steel nozzle and the heated bed —just warm enough to keep the nylon from warping.

“First, we need a good calibration,” Tyler said, tapping the printer’s touchscreen. He showed the young maker how to run a bed‑leveling routine, the machine’s probe gently touching the surface at an array of points. The printer’s LEDs blinked a steady green when the bed was level within microns explained Tyler.

“Now for the print settings,” Tyler continued, pulling up the slicer software. “We’ll print at 0.2 mm layer height, 30 % infill with a 3D honeycomb pattern, and Matthew said we should add a couple extra walls to boost it’s strength. Since carbon‑nylon can be a bit brittle at the nozzle, we’ll keep the extrusion temperature at 260 °C—just enough to melt the nylon without degrading the polymer.”

Michael watched the preview of the lever: the outer shell in a sleek, matte finish, the internal ribs glowing in a translucent blue as the slicer highlighted them.

“It’s going to take about 3 hours,” Tyler warned. “You can use that time to test the fit on your bike with the pine jig Mike made, or you can tweak the model if something feels off.”

“Will you be around?” Michael asked, feeling a twinge of nervousness.

“Always,” Tyler replied with a grin. “Press the red button on the terminal if you need me. I’ll be in the print hub most of the day.”

A First Test Run

Back in the automotive bay, Michael and Matthew assembled the pine jig Mike had cut. It was a simple L‑shaped block with a hole to hold the lever’s pivot pin and a slot for the cable housing. They clamped the broken original lever into the jig and measured the distance from the pivot to the grip’s outer edge.

“It’s 98 mm,” Matthew noted, reading his caliper. “Your new model is 97.5 mm. That’s close enough; we can fine‑tune it later if needed.”

Michael placed the unfinished printed lever—still warm from the printer’s build plate—into the jig. The carbon‑nylon felt surprisingly smooth, the ribs barely perceptible to the touch. He hooked a cable onto the lever and pulled gently.

A faint creak sounded as the lever moved, then settled with a solid snap. The feel was different—crisper, more responsive.

“Nice!” Matthew said, patting Michael on the shoulder. “Let’s do a quick stress test.”

They attached a small spring scale to the lever’s cable, pulling until the lever reached its full range of motion. The scale read 25 N, well within the expected load for a standard bike brake.

“It looks like it can handle the forces just fine,” the man said, his eyes reflecting the satisfaction both the completion of a project and the opening of a mind. “Carbon‑nylon is forgiving, but you still need to keep an eye on fatigue over time, the same as the original. The big difference is now if it wears out in a few years or breaks then you can just make another, you’ve already finished all the hard work. You can even share it on a printing website so anybody else that breaks theirs can easily fix it themselves too.”

Michael inhaled sharply, feeling the weight of his achievement settle like a new piece of equipment in his mind. “Do you think it’ll hold up on a real ride?”

Matthew smiled, his scarred knuckles gripping the jig. “Only one way to find out. Let’s give it a spin.”

The First Ride

The sun had begun to dip, casting long shadows across the parking lot. Michael hopped onto his red Schwinn, the new lever glinting darkly in the fading light. He pulled the brake gently; the lever snapped back with a satisfying firmness. He rode the short loop around the Idea Mill, testing the lever on a gentle downhill and a brisk uphill.

The brake felt consistent, the lever’s grip staying firm even as his hands sweated. He stopped at the edge of the lot, dismounting with a grin that stretched from ear to ear.

“It works,” he whispered, more to himself than anyone else.

Matthew, standing a few steps away with his arms crossed, gave a low chuckle and then strolled back inside.

Community Feedback

The next morning, Michael returned to the Idea Mill to post his design on the community board. He attached a photo of the lever, the CAD file, and a short write‑up of his process. Within minutes, a flurry of sticky notes appeared beside his post.

“Great job! Have you tried a different infill pattern?” – Jenna, senior engineering student

“I printed a similar part for my mountain bike, used PETG instead. Your carbon‑nylon is a much better idea!” – Mark, 34, Mechanic

“What about a small rubber over‑mold for better grip?” – Sam, 23, industrial design major

“I’d love to see a version with a built‑in lights or glow in the dark for night rides.” – Jason Mex, 12, Student

Michael felt a warm surge of belonging. He wasn’t just a kid with a broken bike; he was now part of a conversation, a network of makers each contributing a piece of knowledge.

Later that afternoon, he found Luke again at the coffee nook, the hockey stick now a sleek, slightly curved piece of carbon‑reinforced maple. Luke’s eyes lit up as he saw Michael’s lever.

“Dude, that looks like my sticks cousin,” Luke said, tapping the handle. “Mind if I borrow the design? I could use the geometry to make a small ergonomic grip for my stick too.”

Michael laughed. “Sure thing. We’re all sharing here.”

Mike, who had been oiling the pine jig, added, “If you need a wooden prototype for the grip before you print, just let me know. The wood’s cheap, and you can feel the shape before committing to the filament.”

Tyler, who had just finished a print of a prototype drone propeller, walked over with a steaming cup of his own coffee. “You’ve got the spirit, Michael,” he said, handing over the cup. “Keep iterating. That’s how you go from ‘maybe’ to ‘reality.’”

Erika, delivering a fresh batch of cinnamon‑scented muffins, paused to smile at the group. “Looks like we’ve got a whole team of innovators here. Want a refill? I made a ‘Maker’s Mocha’ for the night‑owls.”

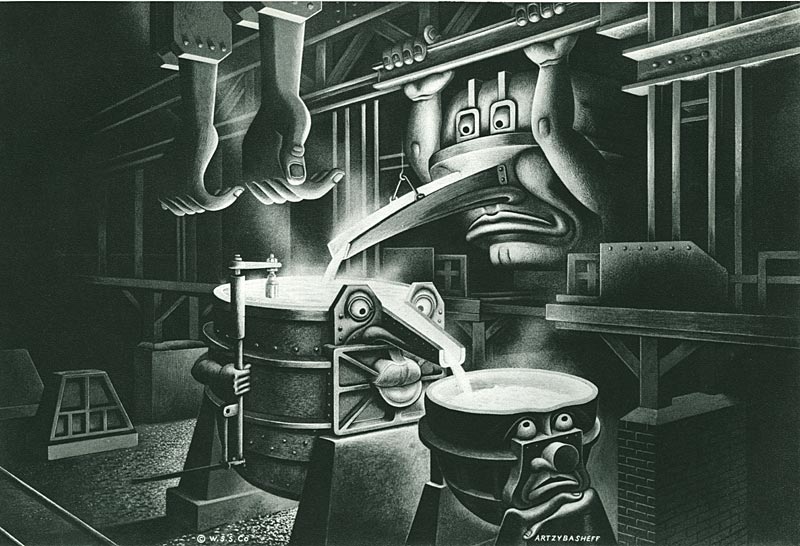

The barista’s eyes met Michael’s, and for a moment, the whole room seemed to pulse with a quiet, collective energy—each person a gear in the larger machine of creation.

The Final Touches

Back at his bench, Michael opened the Fusion 360 file one more time. He added a thin rubber over‑mold—a small ridge on the outer surface that could be printed with a flexible TPU filament, then glued onto the carbon‑nylon lever for extra grip. He also tweaked the cable anchor to make the pull angle a fraction more ergonomic, based on the feedback from the community board.

He exported the new model, swapped the filament spool for a flexible TPU plastic, and sent the over‑mold to the Bambu printer in the 3D printing hub.

When the small part finished, he glued it carefully onto the lever using RTV silicone adhesive, clamping it lightly until the bond set with Mike’s jig. The final product was a sleek, matte‑black brake lever with a subtle, textured band of rubber where his fingers rested—a marriage of strength and comfort.

He snapped the lever onto his bike, gave the brake a firm squeeze, and felt the satisfying click of the cable tension, the rubber grip resisting his thumb’s pressure without slipping.

Reflection

That evening, as the Idea Mill’s lights dimmed and the last few makers lingered over their laptops, Michael stood by the large glass wall, looking out at the city lights twinkling beyond. He thought back to the moment he’d first pressed his hand to the cold steel of the bike rack outside, wondering how he could possibly replace a single broken piece.

Now, holding his own lever—born of charcoal filament, carbon fibers, a pine jig, a community’s advice, and his own curiosity—he realized that the impossible was often just a series of small, doable steps.

Matthew gave a single clap of his hands. “You did good, kid. You turned a problem into a project and a project into a solution. That’s what makers do.”

Michael turned to him, his eyes bright. “I couldn’t have done it without everyone here.”

Matthew nodded, his smile widening. “That’s the point of the Mill. We each bring something to the table—knowledge, tools, a spare moment. And together we make the world a little more possible.”

As the building’s soft hum faded into the night, Michael slipped his new lever into his pocket, already thinking about the next challenge—maybe a sturdier chain, maybe a custom bike frame, maybe something entirely different. The Idea Mill had become more than a space; it was a launchpad for every future invention his mind could dream of.

He stepped out onto the quiet street, the cool air brushing his face. The city’s lights glimmered, and in the distance, a faint sound of a bike’s chain and sprockets turning echoed back toward him.

When he first saw the sign outside it whispered possibility. Now that possibility was growing in his mind and spreading into his life.